By Dr. Jonathan Tiemann

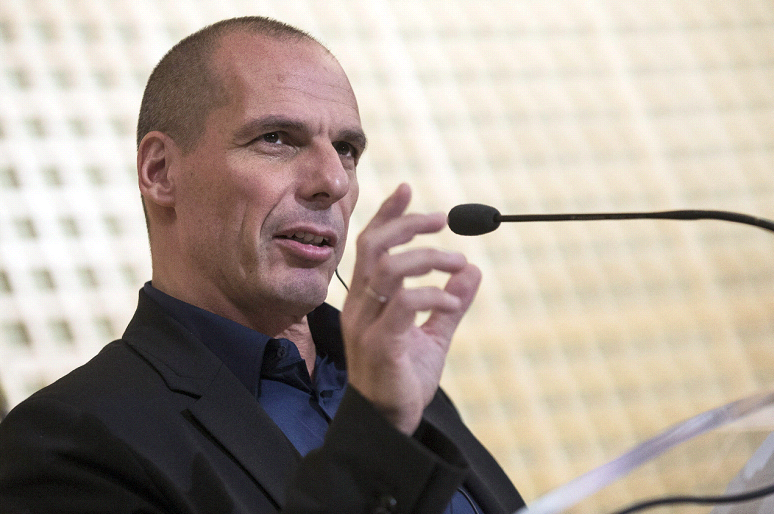

Last month, a general election in Greece brought to power a leftist party called Syriza. Syriza’s leader — Greece’s new Prime Minister — Alexis Tsipras, campaigned on promises to roll back the severe economic austerity the previous government had accepted as a condition for continued financial support from the rest of the Eurozone. But while Mr. Tsipras heads the new government, the new star of the European economic and political scene is Greece’s finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis. Mr. Varoufakis is an academic economist, whose CV includes faculty appointments at the University of Sydney, the University of Athens, and the University of Texas – Austin. The main focus of his academic work is game theory, but he turns out to be a deep thinker and an articulate proponent of left-wing views. He also may be just the man to save the euro.

For much of the ‘00s, Greece’s membership in the Eurozone allowed it to sustain substantial fiscal deficits by borrowing at relatively low rates. By 2010, however, both the country’s public finances and banking system were in trouble, and Greece accepted substantial support (a bailout, if you like) from the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund in exchange for agreeing to adopt a policy of fiscal austerity. This agreement averted an immediate crisis, but at a substantial cost to the Greek economy and people. By the end of 2014 Greek Gross Domestic Product (GDP) had fallen to less than 75% of its 2008 level, and unemployment had risen to over 25%. The January 2015 election results said, in effect, that the Greek people felt that austerity was suffocating them.

The election won’t make Greece’s debt problem go away. The nation’s public debt now stands at around 175% of GDP, an elevated level by most standards. Mr. Varoufakis has only been finance minister for a few weeks, but he has spent most of that time in urgent negotiations with Eurozone institutions in advance of an imminent debt-servicing deadline. As the deadline approaches, Greece and the Eurozone have three basic choices. The first would be an extension of further debt relief on terms requiring negotiation. The second would be a major debt restructuring involving the exchange of existing Greek debt for some other type of security (Mr. Varoufakis has proposed issuing obligations with payments indexed to Greece’s future GDP growth). Failing either of those, Greece might have to resort to outright default, which would likely trigger its exit from the Euro and spawn a banking crisis, a rapid devaluation of Greece’s newly separate currency, and a terrible economic slump. If Greece were to leave the Eurozone, it would establish a precedent that others might follow, destabilizing the entire euro project.

In his writings, Mr. Varoufakis indicates that he has two primary objectives in the current negotiations. He wants to ease the severity of the austerity measures the country’s creditors have imposed, and he wants to keep Greece in the Eurozone. As to the first, he explains that overly severe austerity simply causes unnecessary suffering. More surprising, perhaps, is his determination to keep Greece in the euro. After all, he’s a Marxist, who confesses freely that he would prefer to be promoting a radical agenda. But he’s also a pragmatist, and he fears that the social unrest that could well result from a Greek default and exit from the Eurozone could also spark the type of national socialist movement that brought such horrors to Europe in the 1930s and ‘40s.

Greece’s negotiations with the Eurozone are, inevitably, largely negotiations with Germany. The most important German official opposing further debt relief has been that country’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schaeuble. Other European officials, including senior German ones, have been more sympathetic to Mr. Varoufakis’s position. This suggests that the single person Mr. Varoufakis most needs to persuade to accept his proposals is German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Her calculation will be more political than economic, of course, and the outcome is far from certain. But if Mr. Varoufakis can persuade Chancellor Merkel that she wants to avoid presiding over the disintegration of the Eurozone, he may yet succeed in crafting an agreement that improves life in Greece and saves the euro.

More reading:

Yanis Varoufakis, “How I became an erratic Marxist,” The Guardian, February 18, 2015.

Yanis Varoufakis, “No Time for Games in Europe,” The New York Times, February 16, 2015.

Shawn Tully, “Greece’s fate: In Angela Merkel’s hands?” Fortune, February 20, 2015

Leave A Comment